Species on the Move - Day 1 synopsis

10 February 2016, Hobart Tasmania

This is my take on some of the highlights and main themes from day one of the Species on the Move conference, in Hobart. See also the day 2 synopsis and day 3 synopsis and some lessons learned.

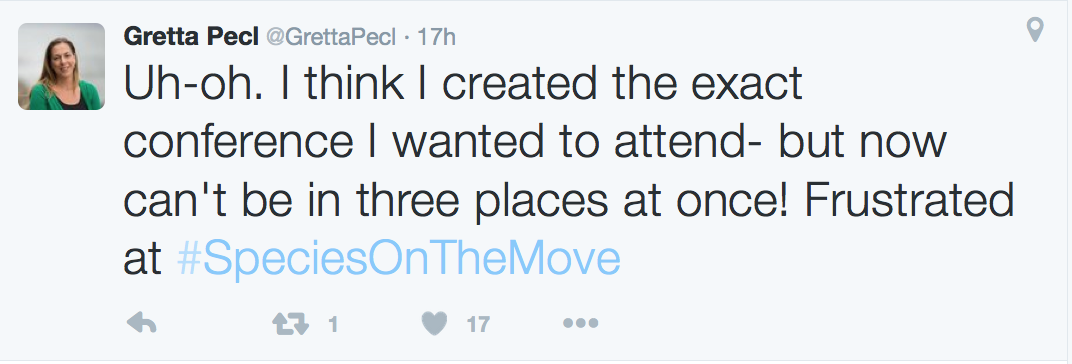

This is my take that is obviously biased towards the talks I saw. I feel your pain Gretta!

It is striking that the ecological effects of climate change are now a personal experience for many people. The ecological impacts of climate change are no longer an abstract concept scientists talk about, or something that happens in models and experiments. I think this speaks to how pervasive the impacts of climate change have become.

We should not underestimate the psychological impact that witnessing climate change has personally

Emma Lee, a Tasmanian Aborigine, gave a passionate talk about how her cultural history in the form of ‘living sites’ or middens was literally being washed away by sea level rise. For a culture that has already lost so much, the further loss of some of their last remaining cultural sites, dating back thousands of years, is devastating. She spoke about the power of science as an outlet to help Aboriginal people tell their story about change over 10 000 years of life in Tasmania. Science can also help uncover some of the lost history of Aboriginals, before it is washed away.

Tero Mustonen spoke about the contribution of indigenous people in Finland to science, through their monitoring of species range shifts and permaforst melting. Locally, in Tasmania Ingrid Van Putten showed that fishers are already attributing the changes they see in fisheries to climate change, well some of them. Which ones they choose to attribute to climate change can be predicted by cognitive biases.

From these talks I learnt that science has an important role to play in helping people communicate their stories and comprehend change.

Climate change is now so rapid that individual scientists have seen their predictions borne our during the course of their careers.

The conference was succesful at attracting broad interest in the media, including from ABC news.

Well, sort of. There are always unexpected ecological outcomes. Camille Parmesan spoke of how she had predicted climate-driven extinction of a butterfly species and it almost did go extinct while policy makers were arguing over what to do about it. The butterfly ended up saving itself by evolving to utilise a new host plant so saved itself.

The conference organisers should be be commended for a series of plenary talks that is representative of both career-stages and gender in our field

I was pleased to see a balanced list of both men and women plenary speakers. This is representative of the relatively young field of climate change ecology where many of the most influential researchers are women (think Parmesan, Elith, Poloczanska, Sorte, Sunday to name a few). Other, more established, fields should aspire to have such a diverse population. Just speculating, but I think other fields suffer from an established, ‘old guard’ who prevent the career progression of younger women (e.g. through sexist reviews). Climate change ecology doesn’t seem to have this problem to the same extent, which makes it a more enjoyable and stimulating field to participate in. The science has benefitted greatly from this diversity too.

It was also great to see some exceptional early career researchers like Jenn Sunday from UBC, included on the plenary list. In her short career, Sunday has become the leading name in the theory of range edges and range shifts. It was great to hear where the research frontiers are from the upcoming generation of climate change ecologists.

On the topic of Sunday’s talk we learnt that Species traits can help predict variation in range shifts.

Climate change ecology has made a natural progression from documenting range shifts to asking why different species vary in the rate of their range shift. Sunday spoke about large range size and omnivory as determinants of more rapid range shifts. She then backed up these findings with solid ecological theories that provide new hypotheses for our field to test.

We should be careful to repeat resurveys, to make sure we don't miss rare species, like this 40-spotted pardalote (striated pardalote also pictured).

Other talks also pointed to the role of species traits in determing rates of range shift. For instance, Jonathan Lenoir spoke about how herbaceous plants were moving faster up elevational gradients than woody species.

Other talks suggested caution in interpreting the data underlying range shifts, myself included.

Morgan Tingley gave us five issues we should consider when comparing historical and resurvey data. He advised caution in interpreting historical data and pointed to the need to thoroughly know your data and check its source. His suggestions included ‘repeat repeat repeat’ - that you should repeat occupancy surveys so you can calculate detection rates of your species and in doing so separate false absences of a species from true extirpations.

We also heard about the mechanisms of leading edge shifts. Mike Kearney in his plenary spoke about a new R package NicheMapR which promises to change the way we do species distribution models from statistical to mechanistic. Dave Schoeman spoke about temperature controls on the leading edge of ghost crabs the ‘ideal’ study species for climate range shifts. Finally, Cascade Sorte talked resolving the effect of ocean currents on range shifts.

That is all I have time to write. I wish I could say more. Before you finish, don’t forget to vote on the video competition!