How should we identify priorities for conservation of biodiversity?

Maps of 'priorities' for conservation are popular product of conservation research. One approach is to make 'hotspots' maps of species richness, or rare species, or rare species that have low protection (e.g. Jenkins et al. 2015 PNAS). However, such approaches defy decades of research on conservation planning.

In a letter to PNAS we explain why hotspots maps of species are not maps of conservation priorities. In fact, calling a map of species richness a map of priorities has been called one of the six common mistakes in conservation planning. Our letter was a reponse to Jenkins et al. 2015, and has created some controversy.

First, everyone from CEOs to life-coaches knows that a succesful agenda requires clear objectives. Without clear objectives, we waste time and money because efforts are not coordinated. Conservation planning is no different.

Second, conservation plans should prioritise actions. Setting a clear objective helps us to define the actions we need to take to save biodiversity. If actions are not prioritised, mistakes can occur, for instance, different actions like conservation easments and setting up protected areas can have very different costs and feasibilities. The implicit assumption when researchers talk about prioritising places is that they are talking about protected areas as the action. If that is the case, then they should be explicit. There are many other actions that can be taken to protect species.

Third, conservation actions are constrained by economic, social and political factors. At least some of these constraints should be accounted for when prioritising actions.

Finally, if conservation aims to protect multiple species, we need to consider how those species are represented across different protected areas. An issue that was first discovered way back in 1983. A map of species richness, may identify two hotspots, but if those hotspots contain the same species, then protecting both of them will not represent all the species in a landscape in the protected areas.

The Jenkins et al. paper, which attempts to set conservation priorities for US protected lands provides a good example of why 'hotspots' approaches are dangerous. A previous analysis, but other authors, that did consider constraints to conservation found considerably different priorities for protection in the US.

A better way

We recently asked how actions to conserve seagrass in the Mediterranean should be prioritised. We considered several actions, including avoiding areas with high coastal development (it was not considered politically feasible to revert coastal development); placing reefs to prevent illegal trawling on seagrass; and placing moorings to prevent yachts from dropping anchor on seagrass. Importantly, we considered the spatial distribution of seagrass, the distribution of threats to seagrass and the cost of stopping the threats. We were able to identify priorities places for each of these actions. It turned out that placing artificial reefs in the best seagrass meadows, despite their high cost, were the most cost-effective way to save seagrass.

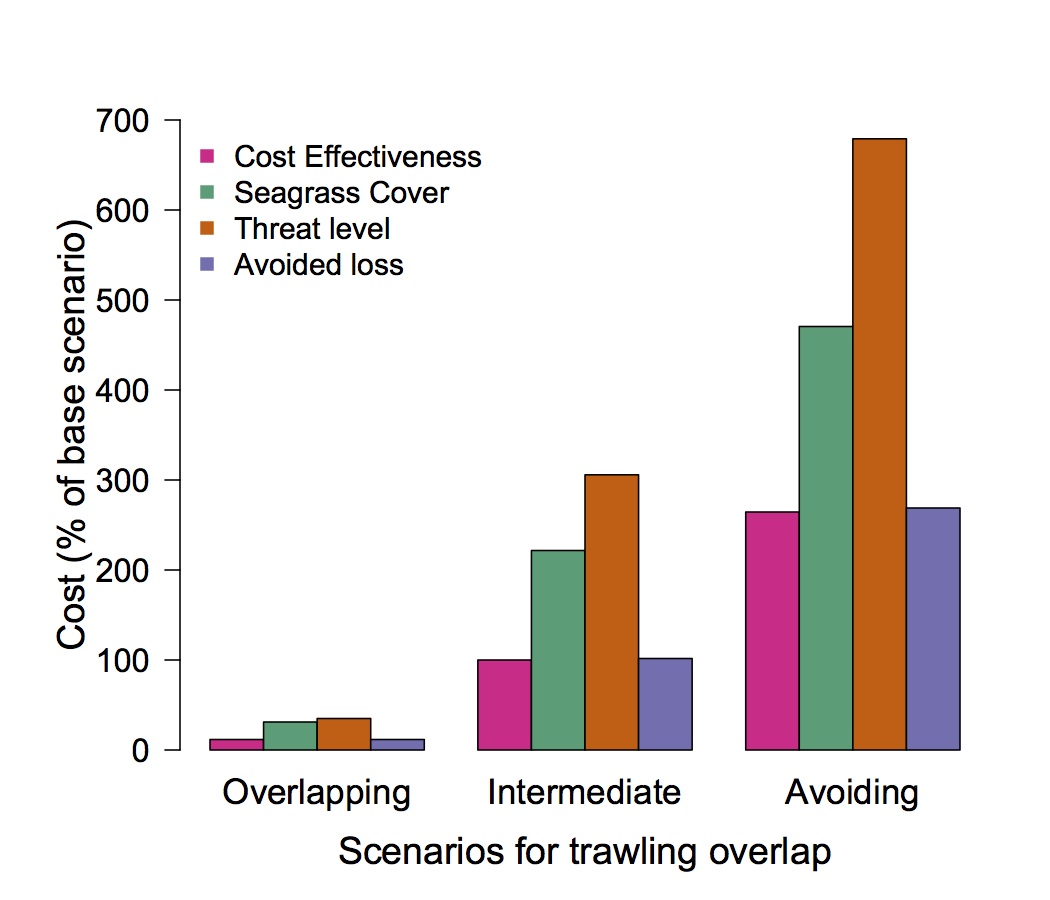

We also compared other approaches to prioritising actions, like prioritising actions in places with the greatest human impacts, and prioritising actions in places that had the most seagrass. We found that not considering the cost of actions could result in plans that were more than two times as costly as the plan that did consider costs (see figure). The plans that used only human impacts or seagrass cover to prioritise actions wasted resources in places that were either not threatened, or should be avoided because of coastal development impacts.

More details: