What is the future of coral reefs?

Coral reef ecosystems face unprecedented threats, but stories of people give me hope for the future

The International Coral Reef Symposium in Honolulu comes on the back of the worst global coral bleaching event yet observed. Global disasters often leave people wondering what hope there is for the future - particularly given insufficient attempts to curb greenhouse gas emissions.

Source: http://twitter.com

Coral reefs will never be the same as they were. I once saw a talk from Charlie Veron about his efforts to create a global coral atlas (at the conference he announced this is now online). He has dived perhaps more of the world’s reefs than anyone. In an incredibly depressing ending to his talk he stated no-one will ever get to experience coral reefs as he has.

Communicating the loss and solutions

Communicating the loss of coral reefs has been emphasised as an important role for scientists at earlier meetings. A few years ago the rhetoric was all about how scientists need to get out there more - engage with public, get in the media, influence policy, be a force on social media. We do all of this now.

I actually met, in person, a professional science communicator at this conference. I am sure scicomm people were around at earlier conferences, but not common enough for me to meet one.

Social media use is a key part of this engagement. Terry Hughes noted in a panel session that every politician has a twitter account, so if they believe it can change people’s minds, we need to be on there too. As an example, Knowlton talked about the incredible success of the []#oceanoptimism](https://twitter.com/hashtag/oceanoptimism?src=hash) hashtag for engaging the public with ocean solutions through twitter.

Social media use at ICRS is orders of magnitude greater than at earlier conferences. Twitter is increasingly popular and the #ICRS2016 hashtag has had widespread impact. A few quick web searches suggest #ICRS2016 had ~240 users and reached over 540 000 people. Check out the #ICRS2016 feed or some of the top tweeters e.g. @OneSwellLife, @physiologyfish and @ultimatemegs to read about the action.

These efforts to communicate were apparent at this conference in a subtle way too - the conversation has moved away from how we need communicate, and instead is now about how we can communicate better.

Peter Kareiva and John Pandolfi both spoke about the need to communicate more of the nuances of science to the media - especially the uncertainty inherent in forecasting the future under different policies. Kareiva used the example of the message box, a commonly used tool for turning academic science into stories for the media or policy. He argued that while this is a useful tool, there it does nothing to help us communicate critical thresholds, impacts and uncertainty - key issues in much of reef science.

In her plenary Nancy Knowlton acknowledged the improvement in communication in coral reef science. However, she implored us to tell stories not statistics. In particularly, stories of people. Terry Pratchett, the sci-fi author once said we shouldn’t be called Homo sapiens, the ‘intelligent human’, but Pan narrans the story telling ape (thanks to Beth Fulton for that quote).

And it is stories of people that give me hope for coral reefs.

Science for solutions

Cinner and colleagues published a paper about coral reef bright spots last week - places where society and managers are doing better than we would expect at managing reef fish (also presented at ICRS2016). ‘Brights spots’ has become an oft repeated meme at this conference.

One of these ‘bright spots’ is Palau and we saw two plenaries about the island nation. The President Remengesau of Palau spoke on day one about the nation’s solution’s orientated approach to reef management. Palau is a world leader in declaring protected areas. Palau’s leadership perhaps stems from a strong traditional management culture. Thus, Palau is a key study area where we can learn about successful management.

I am finding the study of society’s role in management success brings much more ocean optimism than the pure ecological study of reefs.

When I started my career everyone was saying ecological and physical scientists need to collaborate more with economists and social scientists, but barely anyone was doing so. Now things are turning around.

By bringing together social sciences, economists and ecologists we creating a solution orientated science. As Knowlton and others have oft stated, solutions are what give us hope and empower people to take action.

The power of solutions is evidenced in the feelings of colleagues at this conference. Colleagues how primarily attended talks about the recent bleaching event were overwhelmingly depressed about the future of reefs, whereas those attending the numerous sessions on marine fishery management, social science, co-management were more optimistic.

There is growing acceptance that, while reefs will never return to their previous glory, we can make a better future.

In his plenary Pete Mumby talked about the need to study the subtleties of coral reefs. He argued we are facing a future with many ‘mediocre’ reefs, whereas in the past we have focussed our ecological studies on the best of the best, or the worst of the worst. Even degraded reefs can provide services to humans and support significant biodiversity. We need to better understand how management can maximise these benefits.

An important part of understanding trends is documenting the past - so much of which has not been recorded by science. But the past is documented in people’s stories, which Loren Mclenachan, Ruth Thurstan and others are using to push back our understanding . For instance newspaper articles can document historical fish catch (Thurstan) and nautical charts can document erosion of reefs (Mclenachan).

Our future may be dominated by compromises between social, economic and ecological goals. It is hard for the reefs to have their fish and for us to eat them too. Charles Birkeland argued in his plenary that coral reef ecosystems tend to import production not export production. Therefore, they cannot sustain industrial fishing. He talked about Palau’s scenario where its reefs have supported traditional fishing for generations, but the influx of tourists wanting to eat reef fish cannot be supported. Keeping to the solutions theme, he suggested focussing on much more productive pelagic fisheries to support tourism.

The realisation that compromises on ecological quality are needed to support human needs has seen the rise of ‘trade-offs’ analysis. Crow White gave a great introduction to the key steps to trade-offs analysis.

Importantly, trade-offs can help us identify optimal compromises, that are often far better than the status-quo for both people and ecosystems.

Bozec has shown a strong trade-off between harvest of parrotfish and the resilience of coral reefs. However, the right type of management (banning trap fishing) can significantly improve the situation. Aaron MacNeil has similarly found the right type of management is key for fish recovery globally.

Trade-offs analysis is useful for pollution problems too. Kirstin Oleson and her lab are applying trade-offs analysis to ridge to reef management. They are finding that focussing restoration efforts in just a few areas in catchments can be a very cheap way to reduce sedimentation on reefs.

Challenges for coral reef sciences - gender and racial representation

Developments in social science, the study of management and communication give me hope for the future of reefs. However, some ongoing trends in the culture of reef science give me cause for concern.

There are so many women doing amazing work for coral reefs at this conference. So why don't they receive more recognition from our community? Source: http://twitter.com

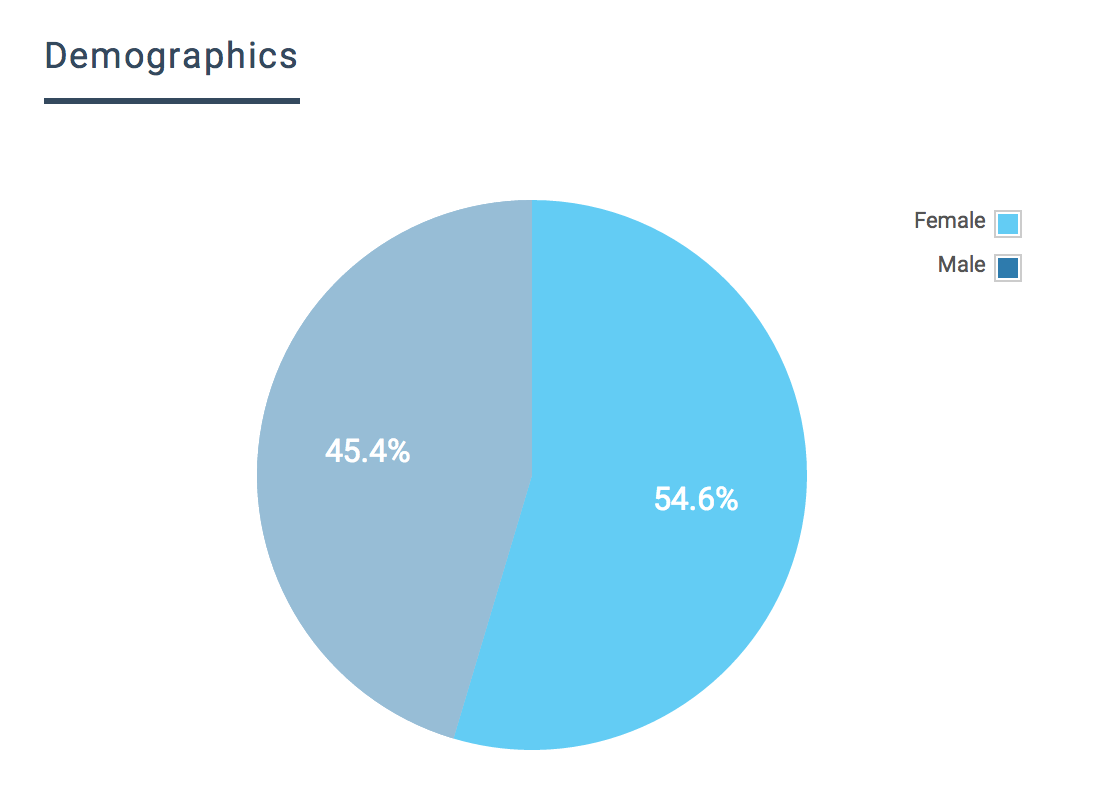

There is still a strong gender bias in coral reef science. Perhaps this is a hangover from the past, however I think it isn’t changing fast enough. I would estimate that talks and attendance at this conference is approximately 50:50, however it is easy to see that women are not provided with the same opportunities in our field as the men.

One story I heard was of a workshop where a senior (male) scientist said he would have liked to have invited more women, but “there just aren’t that many good female scientists to invite”.

Not all sexism is this blatant.

Coral reef science as discipline has a problem with insufficient opportunity for women to receive recognition for their work

The culture of science overwhelming recognises the volume of achievements. Often women have shorter careers than men, therefore the volume of female achievements is often on average smaller. This does not mean the quality of their work is lower. We often seem to conflate quality and quantity when we recognise leaders of our field.

I don’t think there is any lack of ‘good’ female reef scientists. In fact, some of the most compelling talks I have seen at ICRS were given by women (take Lizzie Mcleod’s for example).

It is important to note that both men and women and subject to this bias. I have discussed these issues with both male and female colleagues and both genders often find it harder to think of female leaders of our field.

To give some examples, this year we saw the award of the 7th Darwin medal, the International Society for Reef Studies top award. There has never been a female laureate of the Darwin Medal.

The chance of having no females in 7 Darwin medals is less than 1%

Maybe the award just reflects a historical hangover of what used to be a male dominated field? I don’t think that’s the whole story. We saw a panel discussion on Wednesday night, that was meant to represent some leaders in our field discussing top issues. There were 2 women on a ten person panel.The chance of having two women out of ten people is 5% (reasonably assuming a 50:50 gender ratio at the conference). In science we often treat a 5% chance ‘statistically significant’, so therefore, 2/10 indicates a significant gender bias.

I want to be clear that I am not criticising any individual or organization. I do not intend to discredit individuals who have received accolades - they certainly deserved them. Neither am I criticising the International Society for Reef Studies. In fact, the society’s council has a reasonable gender balance and plenary talks at ICRS are balanced across genders.

Demographics of communicators on the Twitter #ICRS2016 group. Source: http://keyhole.co/preview_new

What I am arguing for is a change in our culture. We could start by creating more formal opportunities to recognise the contributions of women to our field. For instance the International Society for Reef Studies could have an award for female leaders in coral reef sciences.

I suspect their are similar biases in cultural and racial inclusion in our field. I have not been keeping track of those, but ping me if you have useful link.

Informal changes are necessary to change our culture of gender bias. For some tips, check out Jenny Martin’s blog. Top of her list is recognise your own biases.

Coral reefs need diverse participation. It is many of the women of our field who are pushing us forward to find solutions to the problems facing reefs. Follow twitter: there are more women than men communicating reef science there. Many of people who have pioneered social sciences in reef science are also female.

I encourage all of you to value diverse career paths and contributions to our field. As Tallis and Lubchenco have argued the failure to include diverse views is stalling conservation efforts.

A future for coral reefs?

This conference has me both concerned about the enormity of the challenge coral reefs face, but also given me hope that science is contributing to a better future. I wanted to finish with some of the key lessons I have learned here.

-

We can’t always wait for better science. Our field leaders implore us to get involved with communicating to the public and informing management. The science he have now is sufficient to inform a better future.

-

We need to find more nuanced ways to communicate science to the public and decision makers. Often our key messages are lost because they are too dumbed down. Communicating uncertainty is a particularly important, but difficult, challenge.

-

Telling stories about people may be a powerful way to communicate a more nuanced message, that has greater uptake.

-

Coral reefs are of national political and economic significance, as evidenced by attendance at the conference by presidents from three countries.

Email me or get in touch via Twitter if you want to contribute something (full acknowledgement will be given).