Rising seas and coastal development are pushing mangrove forests beyond their historical limits. Predicting how these critical ecosystems will respond is much harder when environmental change is unprecedented. In a new study, Projecting Uncertainty in Ecosystem Persistence Under Climate Change, we show how to estimate the probability that mangrove forests will persist or decline worldwide.

Good predictions of ecosystem persistence are essential for coastal protection, fisheries management and climate-smart conservation planning.

The problem is that traditional models require detailed data that doesn’t exist at global scales. Models predict best when conditions match their training data. Climate change means mangroves face conditions they’ve never experienced before.

We developed a method to estimate probabilities of mangrove persistence using global datasets. This gives us a way to measure uncertainty that we can use to guide conservation decisions, e.g. to identify where management actions are most likely to succeed.

We used network models to analyze how mangroves respond at both their seaward and landward edges. Mangroves are unique because they can potentially expand in both directions as seas rise - landward into newly flooded areas, or seaward by trapping sediment.

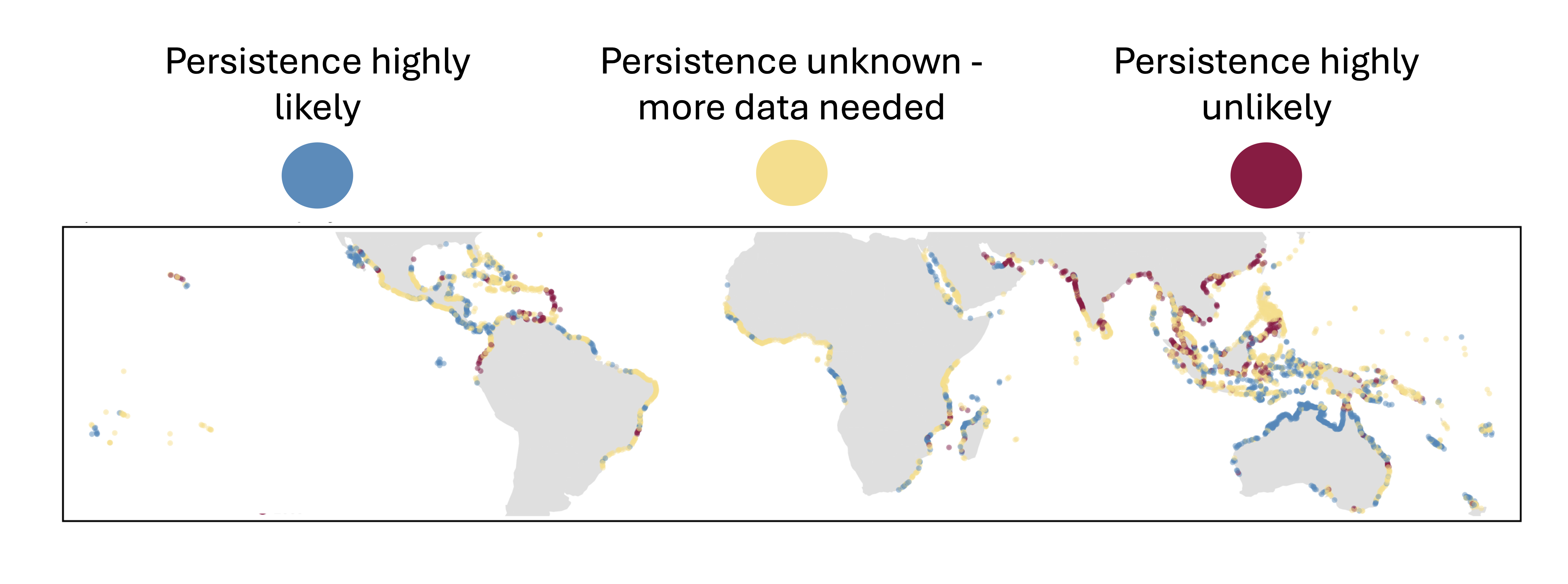

Here’s the projections for persistence of mangroves as they are currently (ie without any loss) from one of our scenarios:

Our models reveal a stark contrast. 77% of mangrove units worldwide are likely to lose area at their seaward edge by 2040-2060. Rising seas, storms and reduced sediment from dammed rivers create multiple pressures. In contrast, about 30% of units could gain area landward, but coastal development often blocks this migration.

Perhaps most importantly, uncertainty is high. In more than half the mangrove units studied, we couldn’t predict whether forests would persist or decline - the probability was essentially random. This isn’t a model failure. It tells us where better data and management actions could tip the balance.

Geographic patterns emerged clearly. Mangroves in areas with small tidal ranges face greater risks. Sediment-rich coastlines offer better prospects for seaward expansion. Areas with dense coastal populations face the greatest landward migration challenges.

We tested conservation scenarios and found encouraging results. With targeted management - sediment addition, barrier removal, and assisted migration - the number of units likely to persist could nearly double.

This research shows a new way to handle ecosystem predictions under climate change. Instead of false precision, we quantify what we know and don’t know. For mangroves, significant seaward losses are likely, but landward gains and conservation success remain possible with strategic action. Read more here.