flowchart LR A[Algal bloom] --> B[Death of animals and plants] B --> C[Decomposition] C --> D[Increased nutrients] D --> A

Ecological modelling is a science geared towards predicting change in ecosystems. But I think for many ecosystems we’ve been going about making predictions the wrong way. We are overlooking how slight changes in feedbacks within ecosystems can lead to runaway outcomes far beyond what we anticipated.

Consequently, we have too much confidence in our ability to build models that predict well.

An alternative way to predict change is to acknowledge and then try to represent high levels of uncertainty in ecological feedback processes. Qualitative models are one way to do this.

Types of ecological models

Increasingly sophisticated models of ecological mechanisms are being used to make predictions ecological change and support challenging management problems like climate change.

One example are the global forest models that are used to predict carbon sequestration from the atmosphere by the world’s forests for the next 50-100 years. Predicting carbon sequestration is essential as it is one part of estimating future atmospheric carbon dioxide, an essential component of the global climate models that predict how much our world will warm.

Statistical models and machine learning are also key areas of innovation. These models tend to focus on describing patterns, over mechanistic detail of the model formulation (though there are exceptions of course). Much effort is invested in developing models that make use of data to capture multiple sources of uncertainty and describe non-linear relationships.

A leading example are the species distribution models that predict where species occur in space. This information is essential for a range of applications, including protected area design, threatened species management and managing species responses to climate change.

What the statistical models that focus on patterns and the mechanistic models share in common is a focus on quantitative predictions. That is, making precise predictions of how much - how much forest, how much carbon, probability of species occurrence and how many species.

What we’re missing

The focus on quantitative predictions puts a lot of faith in our ability to build useful models. For mechanistic models the faith is that we have enough knowledge to know which equations are important. For the statistical and machine learning models the faith is that the data can reveal the important insights.

But what if uncertainty about ecological futures is much greater than we ecologists typically acknowledge?

One example is that marine scientists were totally blindsided by this unprecedented algal bloom that caused people to get sick and killed wildlife along 100s kilometres of coastline. Scientists still don’t know what triggered it.

The importance of feedback processes

Run-away feedback processes often feature in unanticapted ecological change. The algal bloom initiated a run-away feedback process kind of like a zombie plague. It was killing animals and plant life, the decomposition then created more nutrients that further fueled the bloom.

Slight changes in these types of feedbacks can result in drastically divergent futures. Representing different plausible feedbacks and different weights for those feedbacks therefore is one way to get at estimating the range of outcomes for the future.

Qualitative loop models

Loop models are models of feedbacks interconnected systems. They have also been called network models.

Loop models have nodes, which can represent physical or ecological entities such as nutrient concentration, species population size or forest area, and connections, which represent the feedbacks among nodes. Critically, they qualitative predictions of change in the nodes in response to change in other nodes. That is, if one node was to increase will the other nodes increase, stay the same or decrease?

Qualitative models can be extended to model the probability of a positive or negative change. They do this by simulating different weights for the feedback loops, across a distribution of plausible weights.

This creates the possibility of exploring how different feedback processes affect the probability of future increases or decreases in an ecosystem.

Application of qualitative models to a high uncertainty situation

Rising seas and coastal development are pushing mangrove forests beyond their historical limits. Predicting how mangroves will respond is much harder when environmental change is unprecedented. In our study, Projecting Uncertainty in Ecosystem Persistence Under Climate Change, we aimed to estimate the probability that mangrove forests will persist or decline worldwide.

Previous global studies predicting mangrove change have used mechanistic models that make precise quantitative predictions. But I think these models are not honest to the amount of uncertainty we have about mangrove forest dynamics. And the mechanistic models have been criticised for not representing important feedbacks between mangroves and the soils and sediment they grow on.

We used qualitative models to represent feedback processes in mangrove forests.

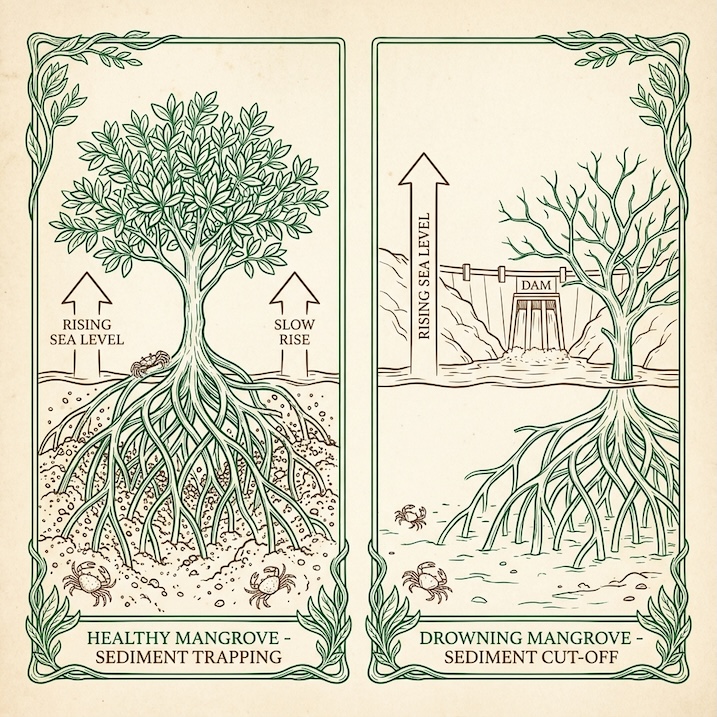

A mangrove that is healthy traps sediment in its root structures. This sediment helps it rise-up out of the water slowly over time, which is key to persistence if sea levels are rising.

Image: Chris Brown with Gemini Pro 3.

But if sediment supplies are cut-off, such as by building a dam upstream, the mangrove can no longer capture sediment to keep up with sea-level-rise. Eventually, the mangrove will be drowned and disappear.

flowchart LR A[Healthy mangrove] --> B[Sediment trapping] B --> C[Elevation gain] C --> D[Persistence with sea-level rise] D --> A E[Reduced sediment supply] -.-> |Breaks feedback| B E --> F[Drowning]

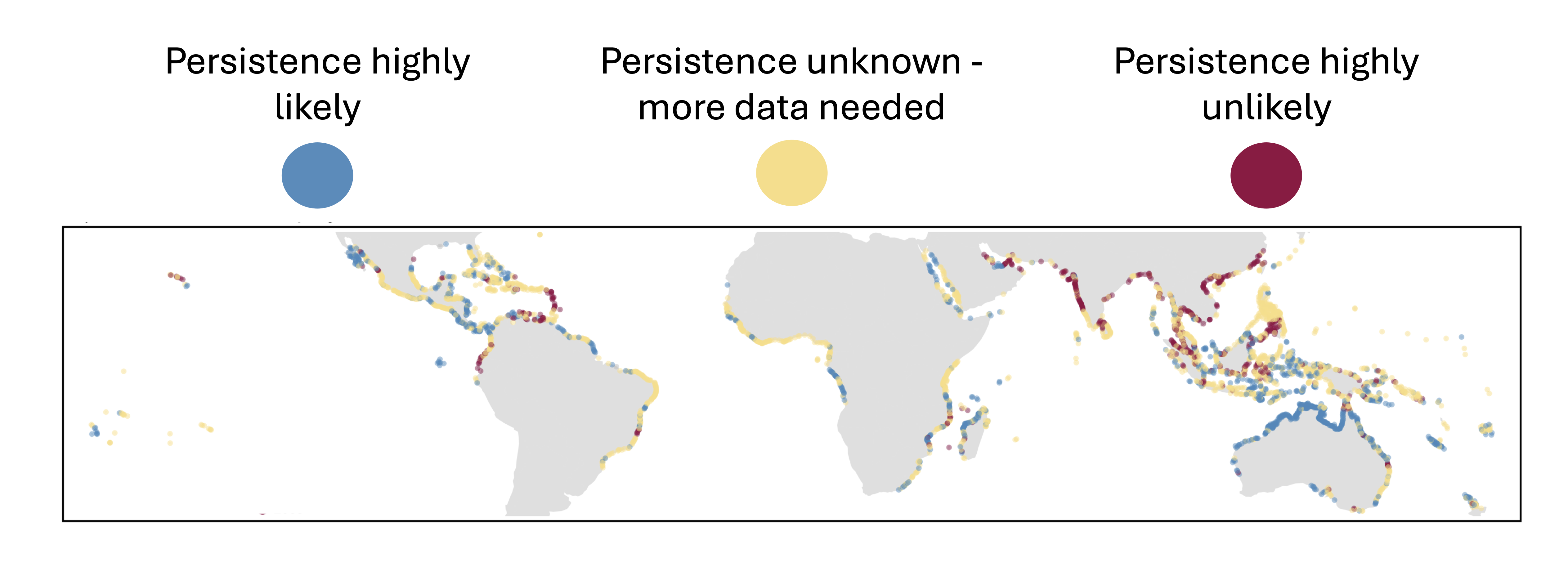

We mapped the loop models to global data on the distribution of mangroves and their threats to make predictions across the world’s mangroves. Those predictions were made under climate scenario modelling so we could account for multiple climate threats.

Here’s the projections for persistence of mangroves from one of our scenarios:

We didn’t stop at predicting the future, we also made hindcasts. This let us validate the model against observations, to get an idea of how certain the model was.

For the future predictions, rising seas, storms and reduced sediment from dammed rivers create multiple pressures that led to predicted mangrove loss. In contrast, about 30% of forests were predicted to gain area landward, as they move inland with sea-level rise. However, coastal development often blocks this migration.

Perhaps most importantly, uncertainty is high. In more than half the mangrove units studied, we couldn’t predict whether forests would persist or decline - the probability was essentially random.

Applications to management and conservation of ecosystems

Useful predictions don’t have to be accurate. It can be more helpful to know what you don’t know. This means acknowledging the uncertainty in the system you are trying to model.

We tested conservation scenarios and found encouraging results. With targeted management - sediment addition, barrier removal, and assisted migration - the number of units likely to persist could nearly double.

Learning where we don’t know enough to make useful predictions is also useful. This isn’t a model failure. It tells us where better data could tip the balance.

Embracing modelling of feedbacks means embracing uncertainty in ecological futures. Doing so will make our predictions more honest and ultimately more useful for management.