Why do species vary in how fast they shift their ranges?

It is well established that species are moving their ranges towards the poles to keep up with global warming. We would like to know how fast species are likely to move, so we can inform policy responses. For instance, how soon will fisheries be affected?

Species on the move is the topic of a major conference this week (10-Feb-2016). There are many talks about identifying range shifts. This is my take on climate range shifts in marine species, based on our recent paper.

We want to know how fast species will move under global warming, so we can inform management policy, such as for fisheries of affected species </a>

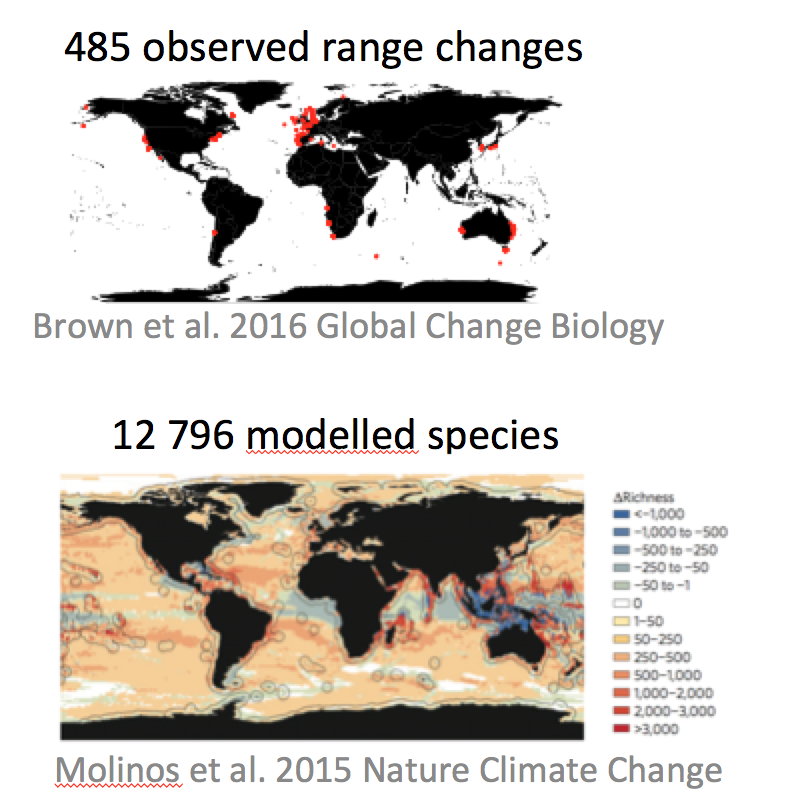

There is considerable variation in how fast different species are moving. What we don’t know is why species vary. This variation makes predicting range shifts in the future difficult. We can build realistic models of almost 13 000 ocean species to predict changes in species richness under global warming, but we have very few observations to test those predictions against (see figure below). While the general trends from the models might be correct, it is hard to fine tune them without more information on how individual species will respond.

We set out to find out why species vary using an analysis of a global database of observed species range shifts. What we found surprised us. We were expecting ecological traits, like a species’ dispersal ability to predict the rate of range shifts. It turned out that the rate of range shifts we measure was more strongly determined by how scientists measured the range shift, than by the traits of the species they measured.

We have the models to that can generate predictions for a large number of species, but we have very few observations of range shifts to test those models against. Finding generalities in species responses, for instance better dispersers may move faster, can help us fine tune the models to get more accurate predictions.

The data we used came from a literature review, that our team conducted during working groups at the National Center for Ecological Analysis and Synthesis. We updated that review and found 485 observations of range shifts, taken from observations of marine species. As a minimum criteria studies had to have observations in the field with a time-span of at least 19 years, to ensure they captured a long-term climate change response, rather than just short-term variation.

We asked two main questions with our database:

-

Do the ecological attributes of a species explain how fast a species range moves in response to climate change?

-

Did the methods used to measure a species’ range affect the rate of the range shift that was observed?

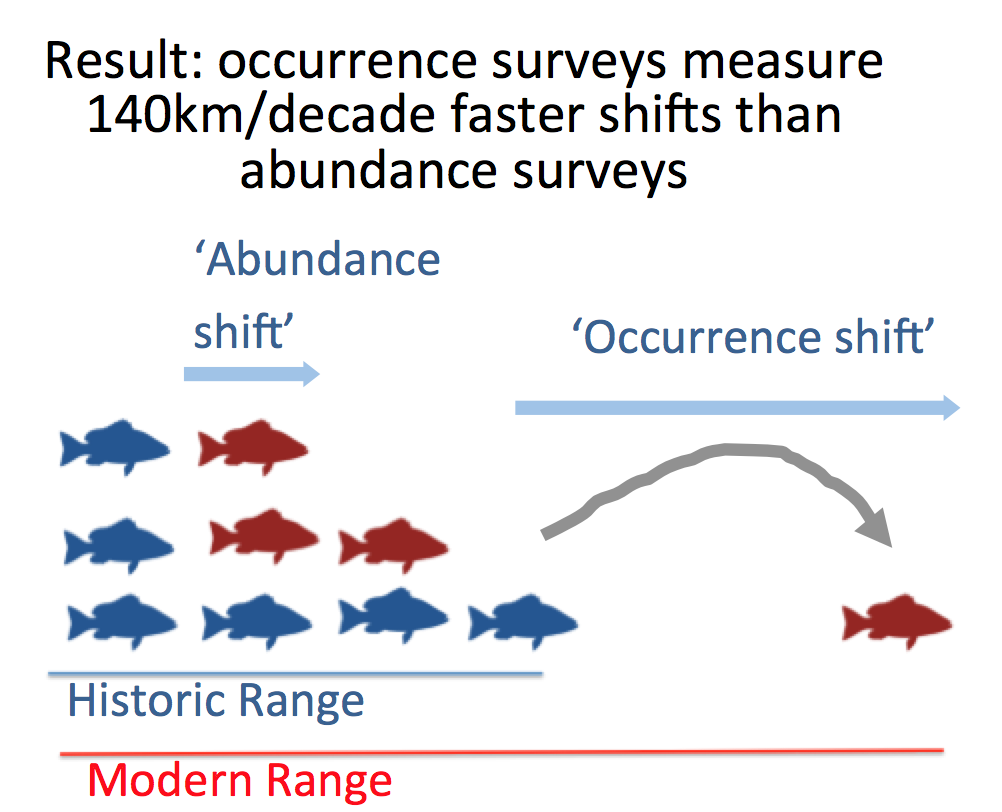

We found the most important predictors of the rate species moved where the type of data (abundance or occurrence) used to measure ranges and how frequently a species’ range was sampled.

Abundance vs. occurrence measurements were important because they measure different parts of a population’s range shift. Occurrence based measures measured faster range shifts than abundance based measures. Occurrence based measures are influenced by the movement of single individuals, who may represent the extremes of movement, not the norm. They likely pick up on the early colonisers that are extending a species range, but have not yet established new populations. These colonisers can move very rapidly. Abundance based measures focus more on established populations. Because population establishment is slower, rates measured by abundance are also slower.

Abundance and occurrence surveys measure different rates of range shift because they measure different ecological processes </a>

Frequency of sampling was also important. Yearly sampled ranges were observed to move more slowly than resurveys - studies that repeat a historical survey in the present day. This difference may indicate a publication bias in resurveys unintentionally picking places where change has been more extreme.

We did find some differences between species’ movements that were attributable to ecological traits. Most importantly, coastal species moved much more slowly than open-ocean species. This may be because coastal species are more constrained in the habitats they can use (e.g. barnacles on rocky shores), so the rate of their range shifts is limited by availability of new habitat to move into.

Our study has important implications for how we measure and interpret range shifts. While there is no doubt species are responding to ocean warming, we need to be careful about how we measure that change.

First, we should be encouraging resurveys in places that may not be strongly warming. Doing so will give us a more comprehensive picture of which species are moving (or not moving) in response to warming.

Second, meta-analyses should control for the methods of studies they analyse. Previous analyses of smaller regions than ours have been successful at identifying traits that predict how species vary. Our analysis encompassed a much broader area (the whole globe), and therefore a broader range of methods for measuring range shifts. If we are going to uncover traits that matter, we need to control for differences in the methods for measuring range shifts in global analyses.

Finally, the design of new time-series to detect range shifts can be informed by our findings. For instance, surveys of species occurrence may be useful as an ‘early warning’ of new colonisers, by picking up the extreme individuals that respond to warming first. In contrast, surveys of abundance may be most useful for picking up on ecologically significant change, to identify when a new species has established populations in an area.