How statistics help us get causation right

Statistics are often maligned. People can play with numbers to bias the way we interpret reality. Or we can find reasons why two events happened at the same time without any real evidence. As the old adage goes, ‘correlation isn’t causation’. But proper use of statistics plays a crucial role in the advancement of knowledge.

Our brains are prone to making up stories to explain chance events. I was lucky to spot this woodpecker on an exceptionally warm day. Next time it is warm, I will be prone to expecting more woodpeckers.

Our human brains have an impressive but limited capacity to detect patterns in nature. We can be very good at finding patterns in nature, for instance, an experienced birder can easily look at a woodland and tell you what types of birds might be found there. But our ability to detect patterns is also very biased. We are very good at detecting some patterns, too good in fact, whereas other patterns we find very difficult to learn.

I was recently reading Daniel Kahneman’s book ‘Thinking, Fast and Slow. Kahneman was awarded a Nobel prize for his work on behavioural economics.

Kahneman describes how our brain uses ‘heuristics’ to detect patterns in nature, and make predictions. Sometimes these heuristics can rapidly generate good predictions, but they can also be strongly biased.

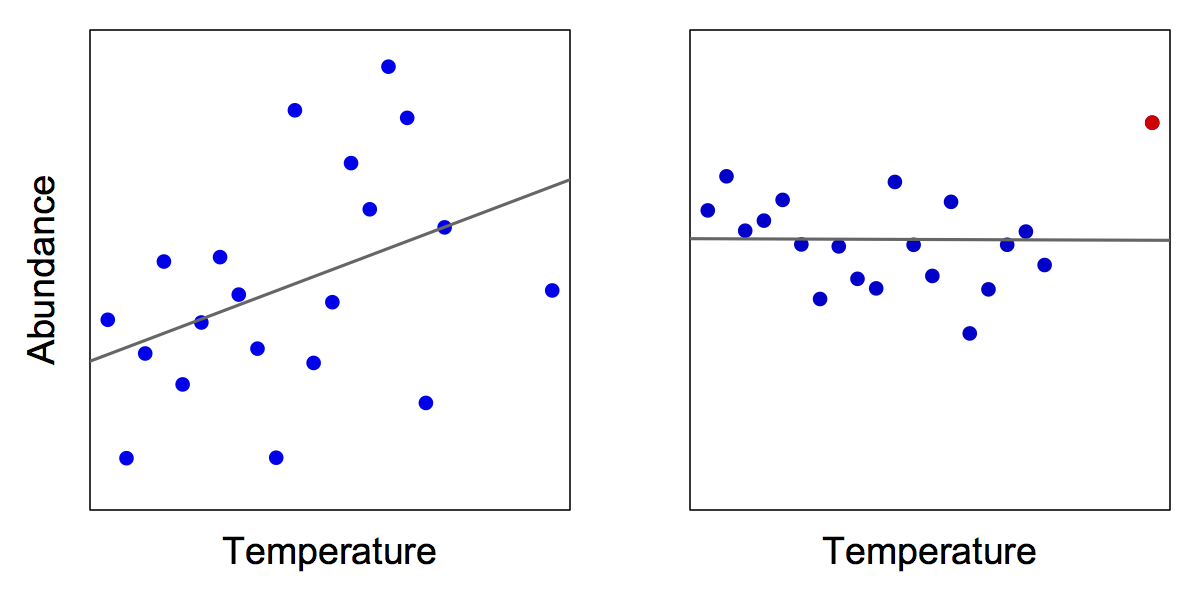

One skill we are particularly bad at is regression. Consider the figure. Maybe you have been going out and counting birds across different times. You think this bird likes warm days, so you will see more of them when it is hotter. In the first figure, there is a correlation between bird abundance and temperature (and by implication, warm days cause more birds to be out and about). However, without plotting this data and perhaps fitting a regression, we would have a hard time detecting this pattern.

Our brains are prone to missing real correlations but then interpreting extreme chance events, like the red point, as causation

In the second figure there is no correlation, but one point stands out as being exceptionally warm and also having a great abundance of birds. We are likely to recall this exceptional event and make a up story about why that happened. Effectively, we would attribute causation without even correlation.

Kahneman goes so far as to suggest a method for ‘mental regression’ if we are trying to predict the outcome of one event, based on another.

Say tomorrow is predicted to be very hot, and you want to estimate the number of birds you might see. We are likely to overestimate the number, because our normal mental heuristic will think ‘hot = more birds’, so ‘very hot = more birds than ever’. But, this heuristic doesn’t account for the large amount of variation in bird numbers not related to temperature (see the figure). For instance, some days a flock of birds might by chance be hanging around, inflating our counts.

The mental regression technique works like this:

First estimate the average number of birds you might count on any day, say 20. Then determine your best guess based on intuition, the number you would expect based on it being very hot. Now guess the correlation between temperature and birds, say 40%. Finally, move 40% of the way from the average abundance toward your first best guess.

We can avoid the pitfalls of our mental heuristics if we use techniques like mental regression. When we can collect data, statistics provides us with the tools to find hidden patterns and avoid the pitfalls of intuitive thinking. Science, and the advancement of knowledge depends on robust statistics. To paraphrase the old adage: Correlation isn’t always causation, but chance events aren’t even correlation.