Protecting forests in Fiji to give coral reefs a future

Many of us become scientists because we have witnessed the degradation of the environment and want to ‘make a difference’. I was therefore excited when the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) asked me for advice on developing a plan for managing the catchments and coral reefs of Vanua Levu, Fiji.

Left: Fish like this Giant Trevally prefer to hunt in clear water. Right: Streams draining forested catchments will carry clean water to the ocean.

WCS is working with communities on island of Vanua Levu, to designate protected areas that will conserve local forests, protect clean water sources and avoid excessive runoff of soils and pollutants that may degrade coastal reefs.

My own career was inspired by growing up on an estuary where I couldn’t eat the local fish I caught, because of heavy metal pollution. The pollution was decades old, a result of decisions made by my parent’s and grandparent’s generations. I wanted to make sure my generation didn’t make the same mistakes.

Yet, the daily life of a university scientist often feels distant from any real change. Most early career researchers are so busy trying to chase funding and write ‘high-impact’ academic publications that they don’t have time to think about ‘real impact’ – science that helps people and ecosystems. The daily struggle to keep a job has often left me wondering if a career in science is really the most effective way to help the environment.

From top: A Bauxite mine in Vanua Levu, the Bauxite is extracted from the top-soil. In the process much soil is released that flows into streams and out to the ocean. A river on Vanua Levu carrying sediment from mining and logging to the ocean. A reef smothered to death by sediment from on land.

The opportunity to advise on management plans for Fiji came through with a Science for Nature and People Partnership working group I have helped to lead (along with Carissa Klein and Hugh Possingham). These working groups are funded by the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) and The Nature Conservancy. They bring together scientists with the conservation staff who are working on the ground with environmental issues.

Major environmental issues and development pressures face the island of Vanua Levu. In particular, agriculture, logging, mining and road development cause soils and pollutants to run-off into streams where they can flow out to coral reef ecosystems. Run-off may be a major threat to coastal reefs and the local fisheries they support.

The hard work done by our WCS colleagues, particularly Sangeeta Mangubhai and Stacy Jupiter, to develop collaborations with communities and government on Vanua Levu meant our working group had a direct avenue to contribute toward environmental planning.

When the Wildlife Conservation Society invited my colleague (Amelia Wenger from Uni of Queensland) and I to present our group’s science at a workshop with community and government leaders, I was both thrilled and daunted. Thrilled, because my science had a chance to inform environmental change. Daunted, because I had never visited Vanua Levu, but would be presenting to local people who live from the land and ocean resources I had studied remotely.

My own contribution before the workshop in Fiji was largely analytical. Our group brought together data from WCS to measure how land-use change has affected stream fish, coral reefs and coral reef fish (e.g. see this recent talk and paper). If I needed local advice on our work I could easily call up my WCS colleagues.

Travelling to Nabouwalu a government centre on Vanua Levu where the workshop would be held, was something of a pilgrimage for me. On the way I finally got to see the ecosystems I had studied extensively on maps and satellite images. We flew over extensive reefs, pristine forest. We also saw the environmental damage the region will face more of in the future – Bauxite mining, logging, pine plantations, agriculture and murky rivers.

Discussing proposals for protected areas with local community members, WCS and Dr. Wenger from UQ.

The objective for the workshop was to bring together leaders from government departments representing these different industries and local leaders from different districts to build a spatial plan across the Bua Province (south-west portion of Vanua Levu). It is also an opportunity for communities to voice their concerns about environmental protection to central government.

Our role was to present our work that showed the connections between land-use change and reef fish. In particular, we highlighted how actions in one district can affect the catchments and marine areas of neighbouring districts.

After our initial presentations we had almost two days for community leaders and government members to discuss proposals for a new spatial plan.

We then developed the spatial and management plans with community members. The plans were designed through discussion around maps with marker pens. All my training in the sophisticated quantitative and computerised methods used spatial planning went out the window.

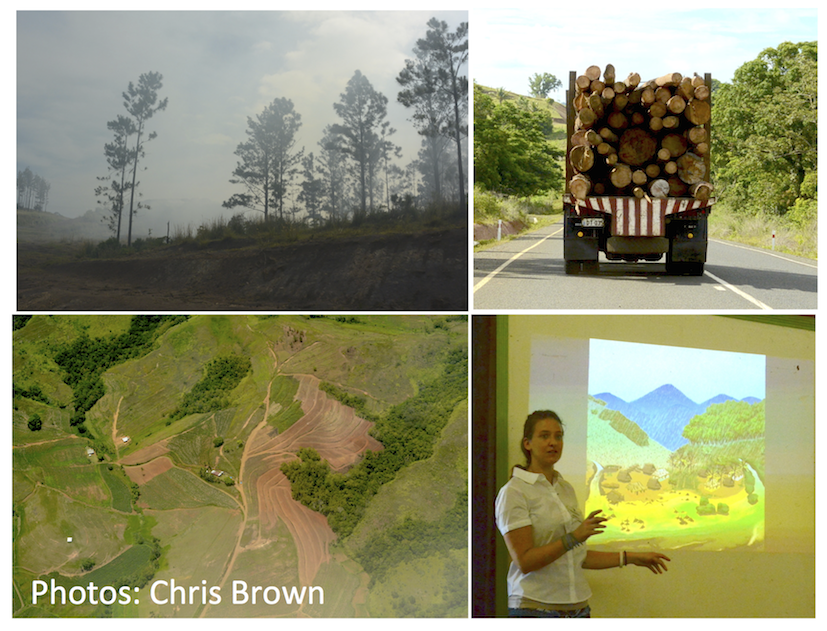

Clockwise from top-left: Fire threatens a pine plantation on Vanua Levu. A truck carries logs to a nearby sawmill. Farmland on Vanua Levu. Dr Wenger speaks at the workshop about balancing nature conservation with logging, farming and development.

You can run the computer programs for spatial planning interactively. However, in this case we had to ask the locals about where the pristine catchments were and where their drinking water came from. We also learned that one large catchment with intact forest on the south-coast had now been largely sold into logging concessions. Sadly, my earlier modelling had identified this very catchment as a major contributor to sedimentation to reefs if it was logged.

Despite the technical simplicity of our approach, we did use many of the principles for conservation planning I had learned over the years. So science did underpin our advice.

For instance, we encouraged community members to identify and protect drinking water catchments – WCS has some evidence that typhoid outbreaks after cyclones are worsened in logged catchments.

Community members also proposed a large ridge-line protected area that linked the land in between many of their districts. We encouraged them to identify at least one intact catchment per district for protection. That way the protected area might also protect connections among the regions ecosystems. For instance, Fiji’s unique fish species that migrate from the ocean to freshwater streams.

Our discussions also emphasised the importance of riparian buffers and suitable road construction to avoid sediment run-off. These principles are already captured in Fiji’s forest practices act, but logging companies often disregard them. A key outcome from our workshop was identifying the need for paid forest wardens, who could ensure forest practices were followed.

One of Fiji’s iconic migratory fish (a goby) is represented on their $10 note.

At the end of the workshop I was exhausted but inspired to see our group’s science getting applied to a real planning process.

Whether real change will happen in the region, we are yet to see. We discovered at this workshop that past protected areas that had been agreed to are now under logging concessions. At the end of the day, it will be WCS and the local people who will play the long-game in finding funding and community support for the new management plan.

Scenes from around Bua Province, Vanua Levu. Clockwise from left: coconut palms, Bua's administrative centre, cleared land and forest adjacent to coral reefs.

I was heartened though, by the closing speech from the local administrator. He said ‘we will not be the guilty generation.’ The Fijian people have lived sustainably in these catchments for generations. He was hoping that his generation could continue to coexist with nature into the future.

Now, I am back in Fiji’s capital city and a brief encounter convinced me the Fijian people have the right mentality to protect their environment for future generations. Last night I was leaving a restaurant in the rain with a colleague and her baby. A group of burly men approached us in the dark car-park. “Baby Jack!” one of them greeted the baby warmly. The others swooned over him, tickling his toes to make him laugh.

In that moment, I saw a country bound by a sense of community and a people who clearly love the next generation. A desire to help the next generation, and the knowledge for how to do so should be all a community needs to make decisions that protect the future of their environment.