Enforcing marine protected areas to reach ecological targets for recovery

Marine protected areas are often implemented without sufficient ongoing funding to ensure their objectives are not compromised by poaching.

In new work we developed models to estimate the cost of enforcing reserves sufficiently to allow recovery of fish species to ecologically functional levels. Importantly, we also estimate the benefits of having community support for reserves.

Jacks in Raja Ampat. Photo: Megan Saunders

This could help management agencies optimise their spending on community engagement activities, like education, versus spending on enforcement against poaching.

(Open access pre-print is here)

In this post I wanted to tell something of the story of how this work came to be.

Inspiration for a model of reserve enforcement

The story of how this paper came to be is slightly unusual and I think, worth telling. It starts, like many good things, in the 1980s.

Some time ago Hugh Possingham (Director of Science at The Nature Conservancy) was describing his PhD work on optimal foraging of nectar eating birds.

Back in the 80s he had developed some models of how a bird would draw down on nectar in a flower. The flower then recharges itself until the bird next visits and draws off nectar again. He wanted to know the optimal timing for the bird to wait before it returned to the flower.

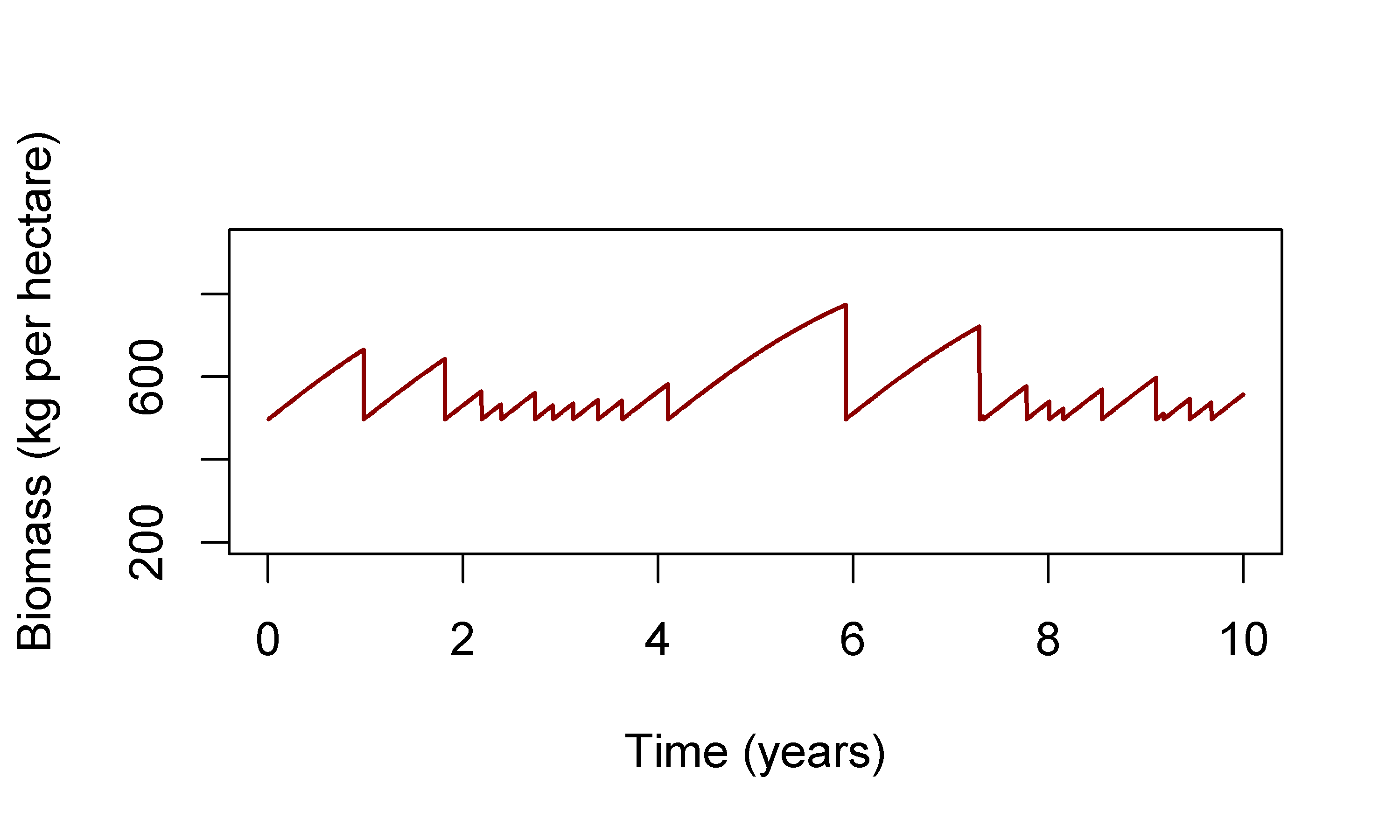

More recently, Hugh had suggested we use this model to predict outcomes for coral reefs under successive cyclones. Corals presumably grow steadily until a cyclone, which knocks them back down again. So what you get is something like in the below graph.

Like all handy models, I stored it away in the back of my head, in case I had reason to use it.

Years later Eddie Game, also of The Nature Conservancy, suggested I look into analysing some data TNC had collected on its reserves in Raja Ampat.

Raja Ampat is the global centre of fish and coral diversity and also the site of a large multi-institutional network of protected areas (that also involved WWF among others).

Fiscally sustainable reserves

The program had been successful in implementing many protected areas and was now moving to a phase where they were looking to manage them with achieve fiscal sustainability.

Obviously a key component of fiscal sustainability is how much you need to spend on costs like fuel for your staff to go and patrol the protected areas. You might also want to invest in educating people about where the reserves are and their benefits.

As a young diver I had been struck by how my local reserves (in Tasmania) could go from being stacked full of lobster to practically empty overnight. It only took one serious poacher to go out and catch a large number of naive lobster.

So when Eddie asked about modelling the Raja Ampat situation I thought back to Hugh’s model of intermittent knock-backs.

Intermittent poaching

And what we ended up doing was modelling poaching as intermittent events that knock back fish abundance (like the bird sucking up nectar), which then recovers slowly in between poaching events.

But we redesigned the model so it was appropriate for fish.

In Indonesia you have fishing boats dubbed ‘roving bandits’ (Here’s a pdf of the original paper). These are large (often international) boats that roam around depleting local reefs of fish before they move to the next location. Unlike local fishers they have no incentive to invest in locally sustainable fishing.

So it made sense to model these roving bandits as intermittent poachers that removed a large biomass of fish.

What the model showed was that you need to ensure poaching by roving bandits is very infrequent to allow fish biomass adequate time to recover to above baseline levels. If poaching was too frequent the reserve would never get anywhere, it was effectively a ‘paper park’.

One problem had me stuck however. I had to specify a parameter to relate the rate of enforcement to the rate of poaching. But I had no idea how to measure or interpret this parameter. Enter an international collaboration.

International collaboration

To test the model out, we used data from Raja Ampat to estimate the rate of poaching and size of local fish populations. Eddie and I brought on study co-authors Gabby Ahmadia (WWF), Purwanto (formerly TNC Indonesia) and Rizya Ardiwijaya (TNC Indonesia) to help interpret the data. I also recruited local PhD student Brett Parker to help with data analysis.

It was great to get to collaborate with this international team and combine our analytical know-how with local expertise on the problems at hand.

An important insight that emerged from this collaboration was the value of local community support. Then it struck me how to interpret the missing parameter - it reflects how much communities support reserves.

If a community doesn’t support a reserve they are more likely to poach, often despite of enforcement effort. Whereas, if the support the reserve they may never poach and even help by reporting on foreign poachers. This insight provided a way to interpret the new parameter I had introduced in turning the bird model into a fish model.

So we used the model to estimate the benefit of community support to improving fish biomass in the reserve. When local communities support reserves they are less likely to poach themselves and may contribute to surveillance by reporting on illegal poachers.

The benefit of community support could also be measured in terms of savings a management agency might make on its budget for enforcement.

So if you get a chance to read the article, take a moment to notice the reference to nectar feeding birds, and the mix of modelling and local insight.

The cost of enforcing a marine protected area to achieve ecological targets for the recovery of fish biomass was published online at Biological Conservation, November 2018

If you can’t access that journal here’s an open access pre-print) or email me for a copy.